A 10th Century Apron Dress

A wealth of information has been gleaned from surviving textile fragments regarding the colour, weave pattern and fibre handling of 10th century clothing, allowing for great reconstructive accuracy to be achieved, should reproductions be attempted. As this adventure is not a formal academic endeavour, the goal of this project is not to produce a precise replica or perfect reconstruction of any one dress, but to end up with an original garment which would not look entirely alien to a time traveller from the target period, using mainly the Ketilsstaðir(1), Oseberg(2), Evebø Eide(3), Hedeby Harbour(4) and Køstrup(5) finds as sources for guidelines on the design and construction of the dress.

The Nutshell Version

What

- 10th Century style apron dress

- Naturally dyed, hand spun Icelandic wool

- Hand woven fabric and trims

- Hand sewn construction and embroidery

Fibre

- Icelandic wool starting as white and mid grey combed tops

– World’s oldest and purest breed of sheep

– Descended from Viking sheep - 30μ fibre diameter, same as many extant period textiles

Dyeing

- Some textiles in period were dyed at the fabric stage, others were dyed at fibre or yarn stage

– Project was dyed at fibre stage

- Blue

– Blue was popular in 10thC women’s clothing

– Ketilsstaðir dress was dyed with woad

– Project wool was dyed with woad and indigo

– Woad and indigo contain the same pigment compound, indigotin, but indigo was not used as a dyestuff until much later in period - Red

– Madder is one of the oldest known dyestuffs

– Project was pre-mordanted with alum

– Dyebath was supplemented with soda ash (sodium carbonate) to increase pH to more basic and shift colour into cooler reds

– Soda ash may not have been used for this purpose in period, but a compound with a high percentage of hydrated sodium carbonate (natron) was known and used in period by glass manufacturers

Spinning

- Z-spun singles as per Ketilsstaðir

– Spun using a spinning wheel rather than period drop spindle due to time constraints

– S-plied warp threads to balance twist and make dressing the loom less of a nightmare due to problems not faced by period weavers

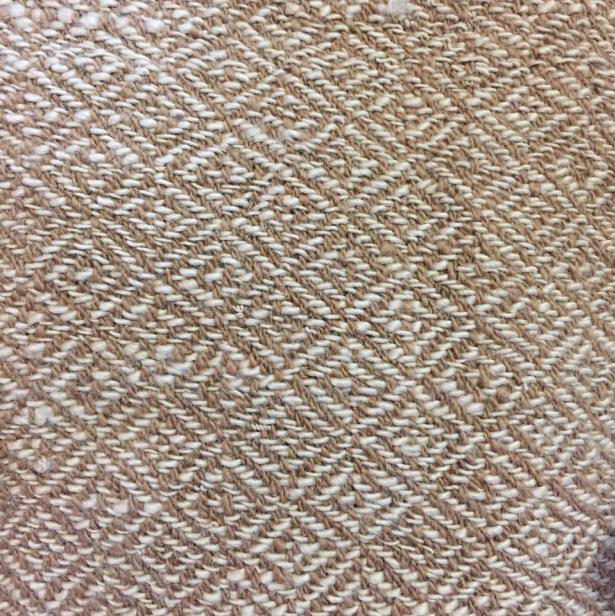

Fabric Weaving

- Woven on a Jack loom instead of warp weighted loom

– Required warp threads to be plied instead of singles - Diamond twill as in period

– 12 ends per inch - Straps woven in 2/2 twill as in period

– Required warp threads to be plied

– 24 ends per inch

Construction

- Geometric piecing as in Hedeby find

- Running stitch and oversewing used for seams as in Hedeby find

- Blanket stitch used to prevent fraying on top unhemmed edge, with tablet woven trim joined by oversewing to blanket stitches as in Evebø Eide find

- Hem folded once and oversewn as in Hedeby example

Trim Weaving

- Køstrup find was woven with two-holed tablets (or at least using only two holes on tablets with more holes)

– The same result is achieved with an inkle loom, though the inkle loom is not period - Tablets would have had to have been made just for the project

- Pattern woven from undyed white and madder dyed orange-red Icelandic handspun

– Pointed motif formed by brocading as in Køstrup and other finds - Køstrup band woven with 14 warp threads, resulting in a band of approximately 13-14mm wide

– Project band woven with 18 warp threads, resulting in a band of approximately 17mm wide, suggesting the spinning done for the project is of the same standard as in period

Presentation

- Presented on a dummy wearing a linen underdress and accessories as worn in period

- Tortoise brooches made by the artisan from dished brass

- Beads as found in many burial sites, including purchased lampworked glass beads, lapis lazuli and malachite beads, and wooden beads made by the artisan, various SCA tokens including a Thor’s Hammer, and a brass dragon carved by the artisan’s consort

- Tablet woven belt

Fibre

The first spark of inspiration for this project arose in mid-2016 when a major supplier of fibre to Studio Sirius offered mid-grey Icelandic wool from an autumn shearing for sale. Further reading into this particular fibre revealed that the isolation and protection of the bloodlines of Icelandic sheep has resulted in a breed which remains genetically identical to sheep bred by early period settlers(6). This suggested that the wool from these animals is likely to be substantially similar to that spun, woven and worn by such women as the Ketilsstaðir grave occupant.

The Icelandic sheep has a double coat consisting of a coarse, strong outer coat, and a fine, soft undercoat. This was also true of sheep in period, and the different properties of the different hairs were valued by textile artisans, with a higher percentage of the stronger outer coat hairs used in warp threads and more of the finer undercoat hairs used to provide warmth in the fabric as weft(7). Analysis of period textiles reveals that much of the wool used was of a ‘hairy medium’ type, of approximately 30μ in diameter(8).

The fibre used for this project was a mixture of naturally white and mid grey wool from autumn shearings of Icelandic sheep. The wool was combed into tops by the supplier, and contains fibres from both the coarse outer coat and the finer undercoat of the sheep, with an approximate average diameter of 30μ.

Interestingly, the white undyed fibre had a softer feel than the grey fibre, but both types were made coarser by the dyeing process.

Dyeing

Blue

Blue is known to have been a popular colour in women’s clothing in this period, and the Ketilsstaðir dress is understood to have been dyed with woad (Isatis tinctoria), due to the presence of the pigment indigotin (with indigo itself unknown to Scandinavia until much later in period)(9). Indigotin is a substantive dye and does not require a mordant, as the dye is able to bond to the textile at the molecular level. However, it is insoluble in water, and must be chemically reduced to a soluble form, which is initially a light green colour (called indigo white). When the dyed goods are removed from the dyebath, the pigment is able to oxidise in the air, returning to blue.

In period, blues were achieved by the fermentation of woad leaves, first to concentrate the indigotin and then again to reduce it to its water soluble form, with wood ash added to increase the pH. Dyed goods were left to oxidise in the open air to turn blue(10). It is unclear at which stage the wool was normally dyed, whether as fibre, yarn, or fabric, but there is at least one example of dyed warp and undyed weft threads(11), and another example from the Oseberg find of a textile that had been dyed at the fabric stage(12). However, evidence for apron dress fabrics which consist of differently coloured warp and weft threads remains elusive.

Unfortunately, woad is difficult to come by in a form ready for use as a dye, and all personal attempts over the last 10 years to grow sufficient woad from seed had failed. As the main difference between woad and indigo is that the concentration of indigotin is much higher in indigo, it was primarily decided that indigo would be an appropriate substitute if dyed only to a depth of shade that woad could achieve (if not quite the same colour), as the source of indigotin would not be apparent in the final product. However, in a stroke of luck, the timing of the start of the project coincided with another round of Icelandic wool sales combined with a woad dye bath which was already being organised by the fibre supplier. This allowed for half of the available grey wool to be dyed with woad, leaving the other half to be dyed with indigo, which would result in a fabric of mixed blues, but not one of starkly contrasting warp and weft.

Indigotin in the form of 60% pre-reduced indigo crystals (soluble in water) was sourced from a company specialising in natural dyes. This form of indigo is normally used with sodium hydrosulphite as a further reducing agent and soda ash as a pH increaser to facilitate reduction. However, in order to reduce the complexity of the project for a novice dyer, and in light of the fact that the wool only needed to be dyed to a light shade achievable by woad, without the need for even dyeing, no further reduction was carried out.

The wool was thoroughly wet in luke-warm water, and transferred to a dyebath containing approximately a tablespoon of indigo crystals dissolved in 8 litres of warm water. The wool was left for 10 minutes and transferred to a clean water bath, where it was left to oxidise for approximately 20 minutes and then rinsed until the water ran clear. The dyed wool was soaked for an additional 20 minutes in a cool water bath containing a small percentage of hydrogen peroxide to neutralise the dye and help with any final oxidation, and a final cool water bath was used to remove any final traces. The wool was then hung up to dry, having somehow avoided any significant felting.

Red

Madder is one of the oldest known dyestuffs, and the main pigment for which it is used is alizarin. Alizarin has been found present in many samples of extant textiles(13), and though it was not the only red dye available in period, it has superior light- and wash-fastness to many dyes. Unlike indigotin, alizarin requires mordanting, which was done in period using alum (aluminium potassium sulphate), which is still used today. Dyeing with madder is very sensitive to pH and the presence of different chemicals. A more acidic dyebath produces better orange-shaded reds, a more basic dyebath produces cool toned reds, and iron and copper substances (including using iron or copper cookware) can dramatically change the results to deep purples and browns(14). Many dyers use potassium bitartrate to increase the uptake of alum into the fibres to be mordanted, but due to the sensitivity of madder to acids, alum was used alone for this project. It is unknown whether soda ash (sodium carbonate) would have been used in period as a modifier, but hydrated sodium carbonate as a component of natron was known and used in period as a flux for glass manufacture, so it is not inconceivable that dyers would have experimented with various chemicals, possibly including natron(15).

The madder for this project was sourced in powdered form as the madder plants which had originally been grown for this purpose were not yet mature enough for the roots to supply a sufficient quantity of alizarin. 100g of white wool was soaked in cold water for an hour to open up the fibres ready for mordanting and dyeing. 8g of alum was dissolved in 4.5L of water in a stainless steel pot before the soaked wool was added. The pot was slowly brought to a simmer and held for an hour, with an occasional prod to ensure even saturation of the mordant into the wool. The pot was taken off the heat and allowed to cool slowly for several hours before the wool was rinsed of any unfixed alum and the dyebath prepared.

The dyebath was prepared with 50g of ground dried madder root, contained in squares of muslin, suspended in 4L of cold water. As a cooler shade of red was desired for this project, soda ash was added to increase the pH of the dyebath until the desired shade was achieved. The mordanted wool was added to the dyebath and the pot was slowly heated until too hot to touch, and kept hot for 2 hours. It was then taken off the heat and allowed to cool overnight. The dyed fibre was rinsed in cool water and allowed to dry.

Spinning

Spinning fibre into yarn is well known to have been done in period using drop spindles, with a multitude of spindle whorls found in many gravesites, including Ketilsstaðir(16). Due to time and proficiency constraints, the wool for this project was spun into yarn using an Ashford Traditional single drive spinning wheel with bobbin-and-flyer assembly.

The fibre was spun in a semi-woollen manner, in which the fibres are largely aligned as for worsted wool, but drafted from a folded section of prepared fibre, which gives a slightly less dense product, as well as being significantly faster than worsted spinning.

Textile finds of the period involve threads spun only into singles, without plying. The Ketilsstaðir find, for example, contained warp and weft threads which were both z-spun singles(17). It is likely that the reason for this is that weavers in period had no need for the thread to be more balanced, and the use of singles rather than plied threads is more economical both in terms of materials and time, and results in a softer, lighter fabric.

It was originally the plan to emulate this technique, but experiments in weaving z-spun singles not only caused significant problems in dressing the loom, but the resulting fabric had a tendency to twist, even after soaking, ironing and blocking. For these reasons, the difficult decision was made to ply the warp threads for the main fabric.

Warp threads for the decorative band were z-spun and S-plied, as per the Køstrup band(18), as was the weft, which is consistent with the brocade weft pattern thread in the Køstrup band. The width of the finished band is commensurate with the Køstrup band width, which suggests that the warp threads were spun to the same standard.

Fabric Weaving

At the time the decision was made to make a garment from scratch, the weaving tools available consisted only of two rigid heddle looms, capable of doing very narrow pieces in tabby weave (or 3-shaft patterns with substantial difficulty). The economy of fabric in the design of an apron dress meant that the tearing out of hair during the weaving process could be kept at a minimum. However, several months into procrastination, a large 4-shaft Jack floor loom with a wider maximum weaving width was acquired, which enabled the production of a diamond twill fabric such as that preserved in many extant fabrics. The different sett that this loom also provided allowed for finer threads to be used, which, while boosting the polish of the final product, also increased the amount of fibre consumed during weaving, so the economical use of fabric in the apron dress was still desirable despite the increased design capabilities afforded by the floor loom.

Having experimented with diamond twills with both plied threads and singles for warp threads, the decision was made to weave using plied warp threads, as the experiment using singles for warp threads was extremely difficult to set up and the finished product had a stubborn twist, which was believed to be the result of the unbalanced warp threads, as the twisting did not occur in the experiment using plied warp threads. The planned sett of 24 dents per inch (dpi) as in period examples was halved to 12dpi to accommodate the double thickness of the plied warp threads. However, it could still be argued that the plied warp maintains a density of 24dpi, only the pattern size follows a sett of 12dpi.

In addition to the diamond twill, the fabric was begun with a short section of tabby weave, both to help spread the warp ready for the patterning, and to emulate the beginning section of fabric woven on a warp weighted loom(19).

The weft threads were spun as needed during weaving to cut down on the amount of work to be done and provide variety in the work. This meant that only 300g of the 400g of woad dyed wool was used for the main fabric, and the remaining 100g could be used for sewing thread and for weaving straps.

When the weaving was completed, with only a few centimetres of loom waste, the fabric was soaked in hot water with a small amount of detergent to open the fibres and set the pattern. The fabric was then rinsed and allowed to dry. The fabric still twisted at the ends, which was unexpected, and new hypotheses for this were formulated, in that perhaps the plied threads were overtwisted, which was not supported by previous plied warp weaving, or perhaps the weft singles were overtwisted, which is the more likely scenario given that a good amount of pigtails (places where singles ply themselves together, leaving small ‘pigtails’ jutting out perpendicularly to the singles thread) had to be unravelled during weaving, with some remaining in the fabric.

The finished fabric measured 432cm long with a width of approximately 32cm.

The straps were woven to approximately an inch wide in a 2/2 twill as in the Ketilsstaðir find(20), but with a single herringbone pattern reversal for interest. Singles were spun from remaining woad dyed wool, but when an attempt was made to dress the loom, catastrophic failure meant that as soon as tension was applied, every thread teased apart and broke. To remedy this, just enough of the singles were plied to create a warp of 25 threads, which were double sleyed through a 12dpi reed to produce a band approximately an inch wide, in comparison to the Ketilsstaðir strap thread density of 22 warp threads per inch. The remaining singles were used as weft.

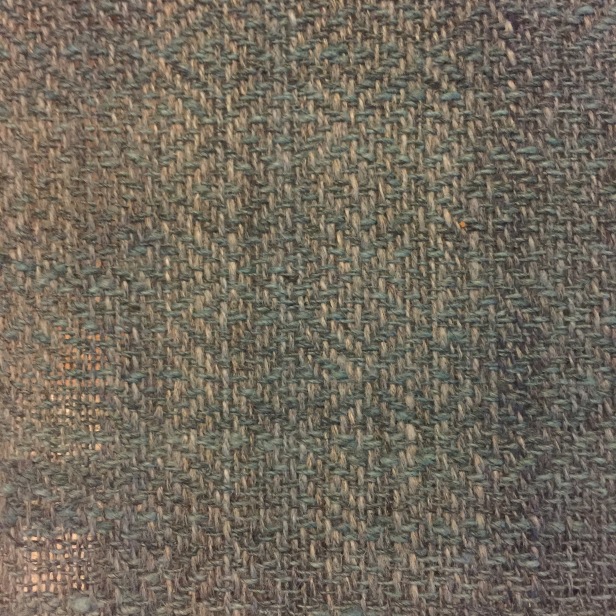

Trim Weaving

Notes from a reconstruction of the Ketilsstaðir dress mention that weaving done on a warp-weighted loom such as those used in period requires a tablet-woven starting band(21). As the reconstructionists used a modern countermarche loom for their project, they decided to add a tablet woven band later, using the extra warp length of the main fabric as pre-attached weft threads for the tablet woven portion. A repeated design reminiscent of the Køstrup motifs was chosen for its simplicity in setting up and to complement the diamond twill of the main fabric. To create a striking design, a quantity of naturally white Icelandic wool was left undyed, and woven with the wool which had been dyed an orange-red with madder.

As the Køstrup piece was woven using only two holes in the tablets(22), it was decided that an easier alternative would be to use a recently acquired inkle loom. Though the inkle weaving is not itself appropriate for textiles of the period, the exact same result is achieved by two-hole tablets used in a back-and-forth manner. As tablets would have had to be made specially for this project, the inkle loom was a convenient alternative. The loom was used to create a pattern of 2 red border threads on each side of a white ground of 14 threads, with a red brocaded pattern in the centre similar to that on the Køstrup piece, which is also present in other finds of the period(23). Unlike the Køstrup band however, the project band did not utilise a ground weft. The width of the project band as compared with the Køstrup band is same (just under 1 warp thread per millimetre), which shows the spinning of the thread to be the same gauge.

Construction

The dress was pieced together from two rectangular sections and two tapered rectangular sections, reminiscent of the piecing done on the find from Hedeby(24), but compromising on shape in order to fit the artisan with the inadvertently narrow fabric that was woven. Unlike the Hedeby example however, the tapering was left incomplete and the fabric darted rather than cut, as the coarseness of the weave left the fabric prone to ravelling even with finished edges.

Running stitch was used to join the pieces, with oversewing used to finish the raw edges and turned hems, and blanket stitch was used to finish the top edge ready for sewing to the decorative band. These stitches are consistent with the Hedeby example(25).

The decorative band was attached to the top edge of the dress by oversewing the trim to the blanket stitches on the edge of the dress, which is consistent with trim sewn to a cloak in a find at Evebø Eide(26), and easier than using fabric warp as weft to weave directly to the fabric, as done by the Ketilsstaðir reconstructionists in their dismissal of the reenactors’ practice of sewing trim to fabric. As this technique combined with rough hand spun wool on hand woven fabric resulted in an uneven finish (valuing stitch security over appearance), chain stitch was used to embroider a line across the join.

Further embroidery to decorate the bottom hem was attempted, but the hand spun thread did not leave a good enough result and was tried and removed three times before the decision was made to leave the hem unadorned.

Presentation

For presentation, the dress has been displayed on a dressmaker’s dummy, over a linen underdress as worn in period, and decorated with handmade tortoise brooches from dished brass, instead of cast bronze brooches as found in many graves(27). Between the brooches are suspended beads of lampworked glass, malachite, lapis lazuli and handmade cedar beads, with tokens of different materials from different SCA events, including a Thor’s Hammer.

References:

1. The Lady in Blue-Bláklædda Konan, National Museum of Iceland Project, https://northernwomen.org/project-2/

2. Ingstad, A, Textiles of the Oseberg Ship, http://www.forest.gen.nz/Medieval/articles/Oseberg/textiles/TEXTILE.HTM

3. Pedersen, I. R, ‘The analyses of the textiles from Evebø-Eide, Gloppen, Norway’, in Bender Jørgensen and Tidow, NESAT 1, pp. 74–84

4. Hägg, I. 1984. Die Textilfunde aus dem Hafen von Haithabu. Berichte über die ausgrabungen in Haithabu, Bericht 20. Neumünster: Karl Wachholz Verlag.

5. Rasmussen, L. and Lønborg, B. 1993. Dragtrester i grav ACQ, Køstrup. Fyndske minder, Odense Bys Museer Årbog.

6. Oklahoma State University, Breeds of Livestock – Icelandic Sheep, http://www.ansi.okstate.edu/breeds/sheep/icelandic

7. Walton, P, 1988, ‘Dyes and wools in Iron Age textiles from Norway and Denmark’ Journal of Danish Archaeology 7, pp144-158.

8. Ibid.

9. Hayeur-Smith, M, The Lady in Blue, https://northernwomen.org/project-2/

10. Edmonds, J, The History of Woad and the Medieval Woad Vat

https://books.google.com.au/books?id=CFgBaArLvWsC&dq=viking+woad+dyeing&source=gbs_navlinks_s

11. Walton, P, 1988, ‘Dyes and wools in Iron Age textiles from Norway and Denmark’ Journal of Danish Archaeology 7, pp144-158.

12. Ingstad, A, Textiles of the Oseberg Ship, http://www.forest.gen.nz/Medieval/articles/Oseberg/textiles/TEXTILE.HTM

13. Priest-Dorman, C, Viking Age Dyestuffs, https://www.cs.vassar.edu/~capriest/vikdyes.html

14. Billings, J, Madder, Mordants and Modifiers, https://woollenflower.wordpress.com/2013/07/11/madder-mordants-and-modifiers/

15. Henderson, J, 2013, ‘Ancient Glass: An Interdisciplinary Exploration’, Cambridge University Press, pp94-110.

16. Hayeur-Smith, M, The Lady in Blue, https://northernwomen.org/project-2/

17. Ibid.

18. Rasmussen, L. and Lønborg, B. 1993. Dragtrester i grav ACQ, Køstrup. Fyndske minder, Odense Bys Museer Årbog, p177.

19. Ingstad, A, Textiles of the Oseberg Ship, http://www.forest.gen.nz/Medieval/articles/Oseberg/textiles/TEXTILE.HTM

20. Hayeur-Smith, M, The Lady in Blue, https://northernwomen.org/project-2/

21. Guckelsberger, M. and Mader, M. The Woman Dressed in Blue: a Textile Find from the 10th c. Icelandic grave and its reconstruction. https://northernwomen.org/2017/02/22/the-woman-dressed-in-blue-a-textile-find-from-the-10th-c-icelandic-grave-and-its-reconstruction-by-marianne-guckelsberger-and-marled-mader/

22. Rasmussen, L. and Lønborg, B. 1993. Dragtrester i grav ACQ, Køstrup. Fyndske minder, Odense Bys Museer Årbog, p177.

23. Ræder Knudsen, L. 1991. Det uldne brikvævede bånd fra Mammengraven. In Mette Iversen (red.): Mammen, grav, kunst og samfund i vikingetid. Jysk Arkæologisk Selskabs Skrifter, p149.

24. Hägg, I. 1984. Die Textilfunde aus dem Hafen von Haithabu. Berichte über die ausgrabungen in Haithabu, Bericht 20. Neumünster: Karl Wachholz Verlag.

25. Dark Age Stitch Types, http://www.42nd-dimension.com/nfps/nfps_stitches.html

26. Ibid.

27. Hayeur-Smith, M. The Lady in Blue, https://northernwomen.org/project-2/

I am in awe.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pfft, ain’t nothin’ to it but to do it.

LikeLike